CHAPTER 8

Cognitive Biases

It has been said that man is a rational animal. All my life I have been searching for evidence which could support this.

On the evening of 3 August 1492, Christopher Columbus set sail from Palos de la Frontera in southern Spain. His small flotilla was made up of a large carrack named the Santa María, his flagship, and two smaller caravels. They stopped first in the Canary Islands to take on board provisions and make some repairs, before turning due west across the wide expanse of the Atlantic. This voyage was to become historic, but not for the reasons Columbus anticipated.

Columbus believed that the route west across the sea to the Orient was shorter than the overland journey east across Asia. He based this on his calculations of the circumference of the Earth and the accounts of explorers who had traversed Eurasia along the Silk Roads. Working from a map sent to him by Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, an Italian astronomer and cartographer, Columbus also believed Japan to lie much further out from the East Asian coast, so it could be used as a stop-off to reprovision his ships after the long sea crossing.

We now know that the numbers Columbus used had simultaneously underestimated the circumference of the Earth and overestimated the breadth of the Eurasian landmass; he also assumed that Japan was much closer to Europe than it really was. By Columbus’s reckoning, there was certainly no room for an unknown continent lying between Europe and China. As far as he was concerned, he wasn’t embarking on a voyage of discovery but undertaking a calculated attempt to reach a known destination by a new route.1

But after a month of sailing west, his lookouts still hadn’t seen any sign of land, and the crew were starting to get unsettled. Columbus knew that he could probably only keep his men in line for a short while longer before he would be forced to turn back or risk mutiny. He figured they must have somehow missed Japan but were surely nearing the coastline of China. Finally, in the early hours of 12 October, after five weeks at sea, they sighted land.

The tale of Columbus’s discovery of the Americas is a familiar one. But what’s less well known are the extraordinary mental gymnastics the explorer performed to maintain his belief that his voyage had actually reached the Orient and not a strange, new land (he had in fact landed in the Caribbean). It’s a clear example of a particular cognitive glitch that can affect us all.

There were clear signs on this first voyage that should have alerted Columbus to the fact that he hadn’t reached East Asia. The interpreter he had brought with him spoke several Asian languages, but he couldn’t make himself understood by the inhabitants of the islands they encountered. Instead of the civilised and cultured people described by Marco Polo, the Venetian merchant who had travelled to China overland in the late thirteenth century, the local populations strolled around naked in a seemingly primitive existence. And once they got over the language barrier, they realised that nobody knew of the powerful and magnificent khan who was supposed to rule China.

Columbus and his men also failed to find any of the valuable spices of the East: cinnamon, pepper, nutmeg, mace, ginger and cardamom. The first day after making landfall, his sailors observed the locals carrying around bundles of dry, brown material, which they initially believed to be the curled bark of the cinnamon tree. But on closer inspection it turned out to be dried leaves. And even more strangely, the locals had the habit of burning these leaves and inhaling the smoke: as we have seen, the sailors were introduced to the habit of smoking – a practice never reported from the Orient. Columbus was never able to locate any cinnamon trees in his exploration of the new lands.

He was also unable to find pepper. The locals did make flavoursome stews with an added spice, but Columbus realised this ‘pepper’ had a very different appearance and taste to that which he had hoped to bring back from China. These New World peppers belonged to the Capsicum family, which includes chilli and cayenne peppers, bell peppers, pimento, paprika and tabasco. Other plants were misidentified by Columbus’s crew. The gumbo-limbo tree was mistaken for the mastic tree, which oozes a valuable resin from cuts made in the bark. Another plant was determined to be medicinal Chinese rhubarb. They also found agave, a rosette of thick, fleshy leaves with spines, and mistook it for aloe.fn12

Columbus made a total of four voyages west across the Atlantic, extensively exploring the coastlines of Cuba and Hispaniola, as well as many of the smaller Caribbean islands and parts of the coast of the Central and South American mainland. But over these explorations, stretching over twelve years, with all their unexpected encounters and findings, he never accepted that he hadn’t reached the Orient at all, but another place entirely. Very little in this new land matched up with the reports from travellers to East Asia. But Columbus viewed everything he saw in the new world through the prism of his own deeply held beliefs. He clung to any scrap of evidence that seemed to support his prior expectations, while any counter-indications that challenged these preconceptions – and there were many – were reinterpreted, downplayed or simply ignored.

Columbus suffered what we would today call ‘confirmation bias’. This is our tendency to interpret new information as further confirmation of what we already believe while disregarding evidence that challenges our beliefs.3 This tendency to resist reevaluating or changing our beliefs once they are established has been recognised as a human trait for centuries.4 As Sir Francis Bacon wrote in 1620: ‘The human understanding when it has once adopted an opinion … draws all things else to support and agree with it. And though there be a greater number and weight of instances to be found on the other side, yet these it either neglects and despises, or else by some distinction sets aside and rejects, in order that by this great and pernicious predetermination the authority of its former conclusions may remain inviolate.’

Five hundred years after Columbus, confirmation bias was also a powerful influence in the production of the intelligence report that concluded Saddam Hussein was building weapons of mass destruction, the casus belli used to justify the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. Iraq did not in fact possess any WMDs, and subsequent investigation into how the case had been prepared revealed that the analysts’ conviction had been so firm that they viewed all information through the prism of their prevailing paradigm. Instead of weighing up pieces of evidence independently, they readily accepted supporting information and simply disregarded contradictory signs, without ever properly questioning their initial hypothesis. For example, a few thousand aluminium tubes purchased by Iraq and intercepted by the security forces in Jordan were determined to be intended for gas centrifuges, equipment used to enrich uranium to weapons-grade. But although the tubes could be employed for such a purpose, the evidence was that in fact they were better suited for conventional uses, such as building rockets, which was discounted. Confirmation bias merely fortified an unsupported presumption and led to war.5

Confirmation bias is also the reason why two people with opposite views on a particular subject or issue can be shown the exact same body of evidence and both come away convinced they’ve been vindicated by it. No matter how balanced and neutral the new information may be, our tendency to cherry-pick the details that confirm our own preconceptions will leave us thinking our own position has been validated. Ironically, it’s the sort of information-processing bias that we can be utterly blind to in ourselves and yet find glaringly obvious and infuriating in others.6

This glitch in our cognitive software is a major cause of the increasingly polarised politics that we find in Britain, the US and the rest of the world today.7 And it’s a vicious cycle: once someone believes that the other side, or a particular media outlet, cannot be trusted and is not presenting a balanced or objective viewpoint, it becomes all the easier to discredit or dismiss their points and arguments.

The problem of cognitive bias is further exacerbated by the search engines and social media platforms from which many of us today source our news and information about the wider world.8 The algorithms underlying these services are designed to analyse what each individual user has clicked, liked, favourited, searched for or commented on in the past, and then start feeding them the content they are deemed most likely to engage with (and share with their own network of online contacts). In this way, our online world becomes an echo chamber feeding us more of the same and in doing so further intensifying any confirmation bias. As a result, many of us nowadays are no longer exposed to contrary ideas or political views. The web is fragmenting into myriad personalised bubbles – it has become the splinternet.

MENTAL GLITCHES

The human brain is an absolute marvel. It excels in computation, pattern recognition, deductive reasoning, calculation and information storage and retrieval. On the whole, it is far more capable than any computer system or artificial intelligence we’ve ever been able to construct. Indeed, considering that our cognitive abilities evolved to keep our Palaeolithic ancestors alive on the plains of Africa, the versatility of our brains to handle mathematics and philosophy, compose symphonies and design space shuttles is all the more staggering.

Despite all these incredible feats, the human brain is far from perfect. While it often performs admirably in making sense of a complex, chaotic world, it can also fail spectacularly. Shakespeare has Hamlet declare that humans are ‘noble in reason … infinite in faculty’, but this patently isn’t true. Our brain has clear limitations in terms of its maximum operating speed and capacity.9 Our working memory, for example, can only hold around three to five items (such as words or numbers) at once.10 We also make mistakes and bad judgement calls, particularly if we’re tired, our attention is overtaxed or we’re distracted. Limits, however, are not defects:11 any system must operate within its own constraints.

But in many cases people make the same mistake in the same situation; the error is systematic and predictable, so researchers can set up a scenario to reliably reproduce it.12 That seems to hint at something deeper – a fundamental part of the brain’s software revealing itself through consistent glitches.

These deviations from how we would expect a perfectly logical brain to function are known as cognitive biases. We’ve explored how confirmation bias led Columbus astray, but there are many other kinds. These cognitive biases can be broadly organised into three categories: those affecting our beliefs, decision-making and behaviour; those influencing our social interactions and prejudices; and those distorting our memories.

They include the ‘anchoring effect’, our natural tendency to base an estimation or decision too heavily on the first piece of information we’re given. This is why the opening figure in a marketplace haggle or a salary discussion can be hugely influential on the outcome. ‘Availability bias’ is the tendency to ascribe greater importance to examples that are easily remembered. For instance, you might feel that flying by plane is more dangerous than travelling by car. But while a catastrophic plane crash may kill a great number of people all at once and is more likely to be reported on the news, the cold hard stats clearly show that, mile for mile, you are a hundred times more likely to be killed in a car than a plane. The ‘halo effect’ is the tendency for our positive impressions of one aspect of a person to be generalised to other unrelated traits of that individual. Then there’s the well-known ‘herd bias’, the proclivity to adopt the beliefs or follow the behaviour of the majority so as to avoid conflict. ‘Rosy retrospection’ is the tendency to recall past events as being more positive than they actually were. ‘Stereotyping’ or ‘generalisation bias’ describes the expectation that an individual member of a group will have certain attributes believed to be representative of that group. And so on. In fact, if you look-up the ‘List of Cognitive Biases’ on Wikipedia, you’ll see over 250 named biases, effects, errors, illusions and fallacies – though many of these are so similar they probably reveal different facets of the same underlying cognitive process.

While not everybody is equally susceptible to all biases, it is certainly true that everyone is affected by them in some way or other. Indeed, an individual’s failure to recognise that they are influenced by bias is a bias itself, known as the ‘bias blind spot’. What’s more, it turns out that even being aware of the existence of a bias is not enough to vaccinate our minds against its effects. Cognitive biases are systemic, intrinsic parts of how our brain works and they can be extremely difficult to counteract.fn2

It is difficult to dispute, therefore, that our mental operating system is beset with a litany of bugs and glitches. What is more controversial, however, is exactly what causes these biases. Why is it that the human brain can deviate so much from what you might expect the rational or logical response to be, and in such predictable ways?

Many of our cognitive biases appear to be the result of the human brain attempting to function as well as it can with its limited computational capabilities, using simplified rules of thumb known as heuristics. These are efficient cognitive shortcuts, a set of time-saving tricks, that allow us to make rapid decisions without fully processing every piece of available data when time is limited or information is incomplete.14 They are both fast (based on simple processes) and frugal (using little information), so we effectively swap a difficult question for an easier one.15 In everyday situations, it is almost always better to make a timely judgement that is adequate than spend ages gathering information and deliberating deeply to try to come to a decision that is absolutely optimised. The perfect is the enemy of the good-enough, and this is particularly true when your very survival may be at stake: a late decision may end up being the last one you ever make. While heuristics serve us well most of the time – at least often enough in our evolutionary history that they’ve helped us survive – they are prone to trip us up in certain circumstances.

Some biases that evolved in our ancestors’ natural environment cause inappropriate responses in the modern world. Take the ‘gambler’s fallacy’, for example. This cognitive bias makes us believe that a random event is more likely to happen soon if it hasn’t happened for a while; or conversely, that an event that has just occurred is less likely to happen again immediately. It’s the intuitive feeling, for example, that if a coin toss has just landed heads ten times in a row, it’s much more likely to come up tails next.

There’s a famous example. On 18 August 1913, in the Monte Carlo casino in Monaco, black came up on the roulette wheel an incredible 26 times in succession. There was a scramble of gamblers trying to get their bets down on red, betting higher and higher stakes in their mounting certainty that the run of blacks simply must stop. But they lost time and time again, and the casino made millions.16 The roulette wheel wasn’t rigged, and in logical terms, each spin had exactly the same probability of black coming up again (48.7 per cent on a European roulette wheel with one ‘0’), regardless of how many times it had come up previously.

Of course, neither a coin nor a roulette wheel has any memory of past events, or indeed any ability to control the outcome of the next toss or spin – each is completely independent of those before. We know this must be true if we think about it logically, but that doesn’t stop the pervasive thought in the back of our mind that our number surely must be due to come up any moment now, to balance things out.

Likewise, there is the ‘hot hand fallacy’; originating in basketball, this is the belief that a sportsperson who has been successful in scoring a basket a few times already will have a greater chance of success in following attempts. Beyond sports, this belief is also held by a gambler convinced they’re on a roll and should keep going to capitalise on their lucky streak before it runs out. Of course, in sports there are reasons why a talented player might be performing slightly better than average, perhaps through gaining confidence after successes in a game. But in most circumstances when it feels like you’re on a hot streak, it’s no more than chance – like heads coming up ten times in a row every now and then.

Both the gambler’s fallacy and the hot hand fallacy have their roots in the same cognitive premise. This is the assumption that similar events are not independent of each other – that there is a connection between separate rolls of the dice, spins of the roulette wheel or shots at the basket. Such an assumption is fallacious in settings like a casino, where extreme care has been taken – the slot machines calibrated, the roulette wheel balanced, the card deck thoroughly shuffled – to ensure that the outcome of the next event is totally unconnected to previous ones. But such truly random distributions were pretty rare in our ancestral environment, in which our cognition evolved to perform.

The natural world is full of patterns. For example, many resources of value to our hunter-gatherer ancestors were not distributed randomly but could be found clustered together: berries on trees, particular plants flourishing in the same habitat, game animals congregating in herds. In these natural circumstances, if you find something you’re looking for, you are indeed likely to find more in the same place.

Thus some cognitive biases aren’t due to some underlying faulty wiring in our brains; they are design features of a cognitive process that has been honed by evolution to fit the characteristics of our natural environment.17 Or you could say that such behaviour is not illogical but ecological.18 It is the artificiality of a casino or experimental set-up in a psychology lab, where randomness has been implemented, that creates an apparent bug in our coding.

Studies of cognitive biases have led researchers to propose two different processing systems in our brains. The first is intuitive and quick, runs subconsciously and employs heuristics for rough and ready responses; while the second is only activated when the task requires it, operates on the output of the first, is analytical and slow and requires concentration. The second system evolved more recently – it is a newer layer of software layered on top of more ancient cognitive infrastructure. The problem is that the first, autonomous system cannot be turned off, and as the second system demands mental exertion, when we’re tired or pressurised we default to the easy, sometimes irrational intuitions of the first.fn3

THE CURSE OF KNOWLEDGE

Humans have evolved a remarkable ability to consider the world from the perspective of another person. This lets us better understand another individual’s motivations and intentions, and so equips us to predict, or even manipulate, their subsequent behaviour. Possessing such a ‘theory of mind’ is a crucial function for succeeding in social interactions and a key step in childhood development. Part of this capability is understanding that another person can have access to different information from yourself, and thus have different beliefs about the world, including some that you know not to be true.

This has been investigated in young children with what is known as a ‘false-belief test’. In the experiment, a scenario is acted out in front of the child that involves a basket, a box, a chocolate and two dolls, Sally and Anne. The doll called Sally places a chocolate in the basket before leaving the room. Anne then takes the chocolate from the basket and puts it in the box. When Sally comes back into the room, the infant is asked where she will look for her chocolate. At around four years old, a child has developed a good theory of mind and recognises that Sally’s information and thus beliefs are different from the child’s own, and that she will try to find the chocolate in the basket even though the child knows it is now in the box.

Despite our exceptional theory of mind, we suffer from a variety of egocentric cognitive biases – tendencies to assume that the knowledge or beliefs held by other people are like our own. One such egocentric bias is known as the curse of knowledge.20 We are persistently biased by our own knowledge and experience when trying to consider how others, with access to different or less information, would interpret a situation and then act. Once we know something, we have trouble conceptualising what it’s like not to know it. In the run-up to the Iraq War, US Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld in 2002 used a now-infamous categorisation of understanding, distinguishing between known knowns, known unknowns and unknown unknowns. The curse of knowledge, however, operates in a fourth domain of unknown knowns – when we don’t realise what we know that others don’t.

We can all recall getting frustrated trying to explain something to a partner or friend who repeatedly fails to understand what we mean when, as it turns out, our description omitted a key bit of information that we’d assumed was obvious. It crops up frequently in everyday life. But in high-stakes situations, the consequences of this form of cognitive bias can be catastrophic.

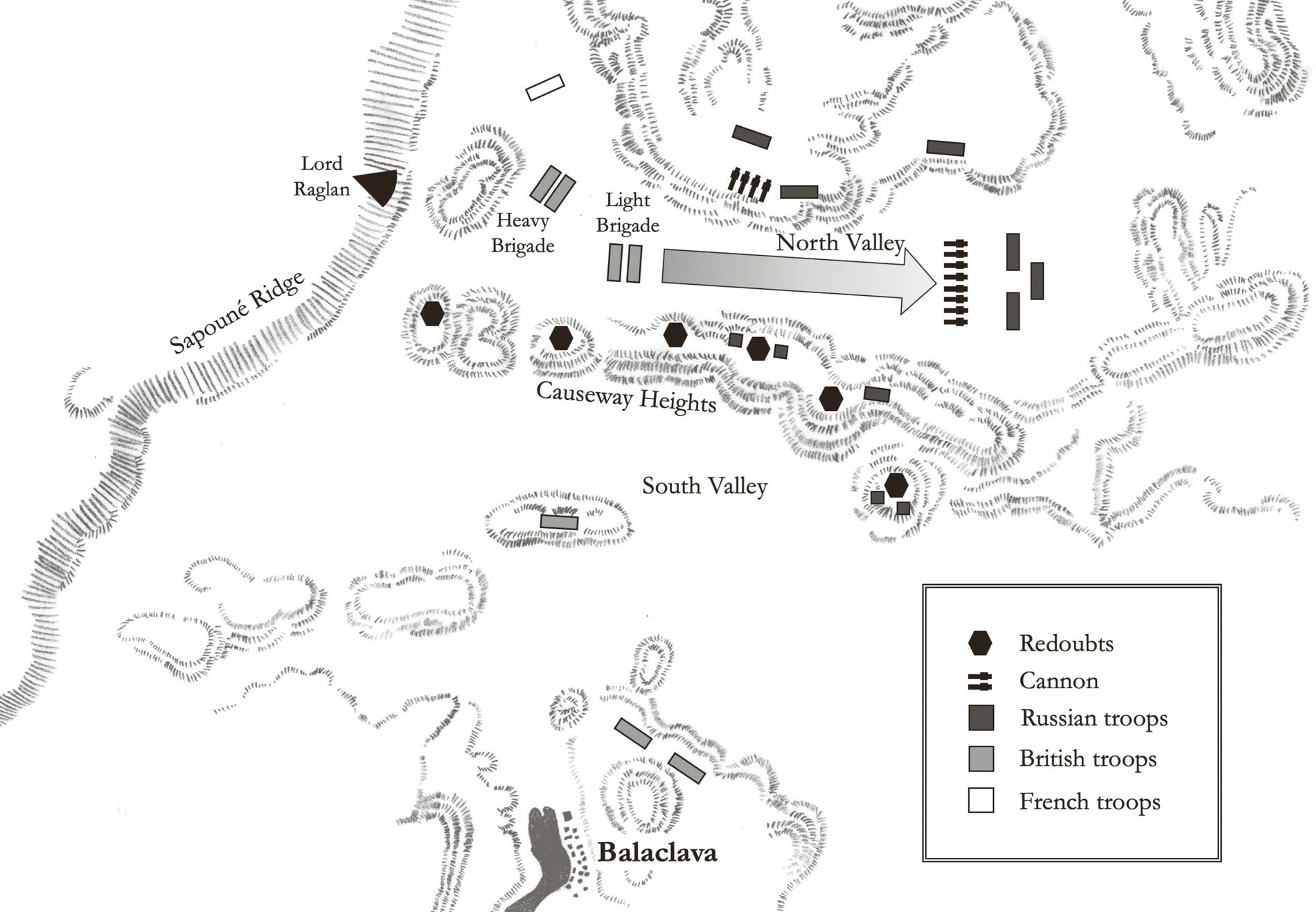

One of the most infamous military blunders in history was the Charge of the Light Brigade in 1854. The Crimean War saw Britain, France, Sardinia and the Ottoman Empire ally against Russia, ostensibly to counter its expansion into the Balkans. During the siege of Sevastopol, Russian’s main naval base on the Black Sea, the British Army found itself on the defensive in the nearby port town of Balaclava.

On the morning of 25 October, Russian infantry had overwhelmed three British earthwork forts, or redoubts, positioned along the Causeway Heights, a low range of hillocks that separated two valleys just to the north of Balaclava. The loss of these positions left that vital port and British supply lines dangerously exposed. The British commander in Crimea, Lord Raglan, therefore ordered his cavalry to retake these redoubts and stop the Russians removing the British cannons positioned there. But peering through his telescope, to his abject dismay Raglan watched his Light Brigade of Cavalry instead ride down the length of the north valley and, in a seemingly suicidal frontal assault, charge straight into the heavily defended Russian artillery battery at the end. Man and beast alike were torn apart by the cannons firing point-blank, and after reaching the Russian position, the shredded squadrons were immediately forced to turn around and retreat back down the valley. Within a matter of minutes, over half of the 676 cavalrymen had been killed or wounded, and almost 400 mounts littered the valley floor.

The foolhardy bravery of the cavalrymen riding into the Valley of Death was immortalised at the time by the poet laureate, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, in his eponymous poem, ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’:

‘Forward, the Light Brigade!

Was there a man dismayed?

Not though the soldier knew

Someone had blundered.’

There had clearly been a disastrous breakdown in battlefield communication, but who exactly had blundered? The episode is often held up as an example of staggering senior ineptitude – but could there have been something deeper behind the tragedy?

Eyewitness reports paint a vivid tapestry of the events leading up to the disaster and reveal how the orders could have become so confused. Raglan issued his first order of the day to the cavalry at about 8 o’clock in the morning: ‘Cavalry to take ground to the left of the second line of redoubts occupied by the Turks.’ This was ambiguous and confusing. There wasn’t a second line of redoubts, and the direction ‘left’ is entirely dependent on the perspective of the viewer. Whose left did he mean? On this occasion, the commander of the British cavalry, Lieutenant General George Bingham, 3rd Earl of Lucan, interpreted correctly and moved his Heavy and Light Brigades accordingly.

Later in the ongoing battle, however, the commands became even more confusing. At 10 o’clock, Lord Raglan ordered his cavalry to advance and take advantage of any opportunity to recover the Heights, using the support of the infantry who were already en route. Raglan believed he had ordered an immediate advance, but Lord Lucan understood that he should wait for the infantry before moving forwards. It was at this point that, peering through his telescope, Raglan saw that the Russians were preparing to remove the British guns from the captured redoubts. Wishing to stress the urgency of his previous instruction, Raglan dictated the calamitous order: ‘Lord Raglan wishes the cavalry to advance rapidly to the front – follow the enemy and try to prevent the enemy from carrying away the guns.’ The written message was given to Captain Nolan, an aide-de-camp and a fine horse-rider, to be conveyed to the cavalry down on the floor of the northern valley. This choice of messenger was unfortunate, as Nolan was hot-tempered and contemptuous of Lord Lucan and his deputy, Lord Cardigan, both of whom he considered dithering aristocrats lacking courage.fn4

When Nolan handed over the written order, Lucan read it with bafflement. The wording was ambiguous and Lucan expressed his confusion over exactly where he was being directed to advance.

‘Lord Raglan’s orders,’ Nolan retorted curtly, ‘are that the cavalry should attack immediately.’

‘Attack, sir!’ exclaimed Lucan. ‘Attack what? What guns, sir?’

Wafting his hand vaguely along the valley Nolan replied disdainfully ‘There, my lord, is your enemy! There are your guns!’

It seems likely that here Nolan had injected his own interpretation – the actual order made no mention of attacking. Raglan’s intentions were most probably only for the cavalry to move towards the redoubts to pressure the Russians to abandon the positions and be forced to leave behind the British guns.

Eyewitnesses report that Lord Lucan stared sternly back at the disrespectful Captain Nolan but didn’t pursue his querying of Raglan’s orders any further. The guns he could see from his viewpoint were those of the Russian artillery position glinting at him from the end of the valley. After some hesitation he issued the order to Lord Cardigan to charge the enemy. The light cavalrymen knew that they would be riding out to meet almost certain death, but those were their orders and they had to be obeyed.

All three of the main characters involved carry a portion of the blame for the mortal disaster that ensued. Lucan ought to have pushed further for clarification instead of charging headlong into the Russian cannon position. Nolan should have been less insolent and goading, ensuring that his commander’s orders were correctly interpreted. And Raglan, for his part, could certainly have communicated his orders more precisely. But the ultimate, underlying factor that spelled doom that day seems to have been a cognitive bias.

Raglan hadn’t even considered there could be any ambiguity about what he intended. He knew what he meant. How could his clear orders possibly be misconstrued? In his mind, the final order was obviously a follow-on from the previous one: Lucan was to advance along the Heights and recapture the redoubts with their British guns. But Lucan had no way of knowing that this wasn’t a separate order designating a new objective. Furthermore, Raglan was positioned atop the Sapoune Ridge at the top end of the valley, and from this elevated vantage point he had a panoramic view across the entire battlefield. From his point of view (literally!), the intended targets were obvious and his orders were perfectly clear. But what Raglan had failed to take into account was that on the valley floor, Lucan’s perspective was much more limited. Lucan’s view of the captured redoubts was obscured by the hilly landscape, and he couldn’t see the guns Raglan was referring to.

While his intentions were clear to himself, Raglan had failed to consider that he and Lucan had access to different information. He was blind to the fact that his orders could be interpreted in a very different way. The Light Brigade was slaughtered by the curse of knowledge.21

The Charge of the Light Brigade is a classic example of what has come to be known as a common ground breakdown. This term describes how two people trying to communicate and coordinate their actions can, without realising it, be working with different information and thereby lose their common ground. In this case, Raglan, suffering from the curse of knowledge, failed to consider that Lucan may not have had access to the same information and battlefield views as him. Indeed, Lucan didn’t have the crucial knowledge that the Russians were preparing to remove the British guns from the captured redoubts but also didn’t realise that he was supposed to have that knowledge – that he might be missing some information. So when Lucan didn’t request that information from Raglan, this in turn led Raglan to conclude that Lucan already knew. Out of this initial curse of knowledge, a whole cascade of incorrect inferences followed. The two men failed to realise that there was a fundamental mismatch in their beliefs. From Raglan’s point of view, Lucan’s subsequent actions were utterly baffling.22

The Charge of the Light Brigade was a notorious military disaster borne of the curse of knowledge. But the underlying cognitive bias doesn’t just influence our assessment of the beliefs held by other minds; it also clouds how we consider our own past beliefs. Often, insights based on new information make us unable to appreciate why we previously believed something different. This distortion of our memory also manifests as the ‘hindsight bias’. This is the tendency to perceive a past event as having been more predictable than in fact it was; this, in turn, can make us overconfident in our ability to predict the outcome of future events. This cognitive bias plays a crucial role in a particular literary genre.

Most of us enjoy a murder mystery or whodunnit. It is a popular form of storytelling where the narrative slowly builds up to a big denouement when the unexpected identity of the killer is revealed. There is often a surprising twist delivering a key piece of information about an event or character that seismically shifts our perspective on the entire story. The conclusion is satisfying, and in retrospect all the signs were there clearly enough.

But this narrative device presents a deep problem for the writer. How do you engineer a twist that is genuinely surprising to the audience, but which also fits naturally with the information already presented so that it doesn’t appear as a fudge or cheat? The challenge faced is to sprinkle throughout the narrative enough clues whose true significance only becomes apparent at the conclusion – seeds that have to be planted firmly enough in the reader’s mind that they are remembered when the denouement is delivered at the end, but which are subtle enough so not to alert the reader prematurely and give away the solution to the mystery.

This is where the curse of knowledge comes in. Once this additional, perspective-shifting piece of information is revealed, and the previous clues are reinterpreted in a new light, this cognitive bias gives you the impression, in hindsight, that the ending was possible to predict all along – indeed, that it was all glaringly obvious when you come to think about it. Knowing what you know now, the signs were all there in plain sight and you can’t imagine how you missed them previously.

This cognitive bias is exploited masterfully by mystery writers like Agatha Christie, whose The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, published in 1926, is widely considered to be one of the most influential crime novels ever written. The plot involves Hercule Poirot investigating the murder of a friend with a new assistant, who serves as the narrator of the story. A breathtaking plot twist is delivered in the final chapter, like a rug pulled from beneath the reader’s feet, when it is revealed that – spoiler alert! – the assistant, who as the narrator the reader has grown to trust, had in fact been the murderer. The same narrative device is used by Vladimir Nabokov in Pale Fire (1962) and Jim Thompson in Pop. 1280 (1964). In cinema notable examples include the dawning realisation of the actual identity of criminal mastermind Keyser Söze in the film Usual Suspects (1995), and the twist endings delivered by director M. Night Shyamalan. In each case, all the clues had been there, hidden in plain sight by the clever misdirection of the writer, but the curse of knowledge taints our retrospective perception to make them appear as if they had been obvious all along.23

CONCORDE DEVELOPMENT

Cognitive biases affect each of us individually, but they also have a powerful influence on decisions made collectively.

In some circumstances, judgements made by a group of people are far more accurate than those made by any one of its individual members. For example, in a common game played at summer fairs, a giant glass jar sits atop a counter, crammed with brightly coloured small sweets, challenging you to correctly guess how many there are. The winning guess will of course be an almost complete fluke. It’s impossible to actually count all of the sweets inside the jar – you can only see those ones pressed against the transparent sides – and although you could make a fairly good, educated guess, this will only get you into the right range. But if you’re lucky, no one else will have guessed any closer than you.

What’s really interesting, though, is that if you look closely at all the guesses that were submitted, there’ll be a broad spread: most in the right ballpark, with others off by a fair bit and a handful that are wildly off. This sort of distribution – known as the bell curve – turns up all over the place: from heights or IQ scores in a national population to the number of frogspawn laid by each female frog in a pond or the probability of getting a given number of heads when tossing a coin hundreds of times. In the case of guessing the number of sweets, the distribution is due to statistical variance between individual estimates, but the key point is that these fluctuations or errors are essentially random, and so over a large number of guessers, the higher and lower estimates tend to cancel each other out. If you take the median of the whole distribution of guesses – the value that lies exactly halfway down the list after you’ve sorted all the guesses into numerical order – you often end up with a number astonishingly close to the actual answer.fn5 This is known as the wisdom of the crowd. Any given individual probably does pretty badly, but in a large pool of independent guessers, the scatter of errors converges towards a remarkably accurate answer.

On that basis, you might anticipate that other judgements and decisions made by a group are also more rational and less affected by cognitive biases. However, the problem with the biases inherent in all our brains is that they are not random: they are systematic. As they work in the same way for each of us, an aggregate will not cancel out the errors. Indeed, if anything, cognitive biases can serve to amplify them.24

In the late 1950s, aeronautical engineers in both France and the UK began working separately on plans for a bold and completely new kind of aircraft: a supersonic passenger jet.

It’s hard to overemphasise just how staggeringly ambitious this endeavour was at the time. The first passenger jetliners had only entered service at the beginning of the decade, and the only aircraft at that time capable of exceeding the speed of sound were small fighter jets with one or two crew members. Even they could typically only fly supersonic for very short periods, before these enormously fuel-thirsty machines needed to land again. And along came this hare-brained idea to build a commercial jet for 100 or more passengers in armchair and champagne comfort, cruising at supersonic speeds of up to Mach 2 – twice the speed of sound, or around 2,200 kilometres per hour – continuously for over three hours. Both Britain and France began developing their own supersonic transport plane, but these two parallel projects were combined in 1962 when a bilateral agreement – a concord – was signed between the two countries. But even from the early stages, the development of this bold new supersonic aircraft was plagued with problems and setbacks.

The technical challenges themselves were formidable. The very fact that it was so very unconventional meant that much of this new Concorde aircraft had to be designed from scratch. The wings needed to generate lift for stable flight at around 2,200 kilometres per hour as well as at 300 kilometres per hour for landing. The engines needed to be fuel efficient enough so that the aircraft could fly for hours. The plane needed a computer-controlled system to continually adjust the flow of supersonic air through the engine intakes and a much more comprehensive and sophisticated autopilot. Flying that fast, the outer layers of the aircraft would heat up to about 100 °C, which meant that the metal airframe needed to be able to accommodate expansion of up to 30 centimetres. Engineers also had to ensure that the fuel tanks didn’t spring leaks with all the flexing of materials, and hefty air conditioners were needed to protect passengers and crew from the heat. Concorde was fitted with afterburners to help give it the extra shove needed for take-off and to push it through the sound barrier. At the low speeds needed for approach to landing, the aircraft needed to significantly pitch up, and so in order for the pilots to be actually able to see the runway, the entire sharply pointed nose was mechanically rotated to droop down. And all this needed to be designed and tested, using scale models in wind tunnels, at a time long before detailed computer simulations were possible.

While all these technical hurdles were causing delays and cost overruns, the financial viability of the aircraft – if it could ever be completed – was also being cast into doubt. Due to the nuisance of sonic booms, in 1973, the US pre-emptively banned supersonic commercial flights overland,25 which scuppered the Concorde’s hopes of running fast services between American cities on the east and west coasts. It became clear that this new aircraft would be restricted to routes over oceans or other unpopulated regions such as deserts. Last but not least, the rising costs also called into question which airlines might actually want to purchase the aircraft when it was completed.26

By the time the Concorde project was finally completed in 1976, fourteen years after the signing of the Anglo-French development agreement, the costs had ballooned. The original cost estimate in the early 1960s had been £70 million (equivalent to £1.42 billion today) but when the aircraft was eventually delivered, the total cost of the program had swollen to around £2 billion27 (equivalent to £13 billion today).28 The costs of research, development and production could never be recovered.29 Only fourteen Concorde aircraft were ever sold, and only to the state airlines of the two countries involved – Air France and British Airways – with their governments agreeing to cover the support costs of the aircraft.30fn6 Concorde was a marvel of aeronautical engineering but an economic failure for the parties involved in its long and expensive development.

It’s not unusual for R&D programmes or construction projects to experience unexpected delays or cost overruns, but in any endeavour that meets substantial problems there is the recurring question of whether it is worth pushing on or better to cut losses and terminate the project. In this case, surely, once the extraordinary technical challenges of supersonic travel and the burgeoning development costs had become apparent, and when the market for the new aircraft was shrinking, the Concorde should have been abandoned as a commercial venture. But the two governments financing the project decided to continue because they had ‘too much invested to quit’.33 And, of course, Concorde had become an issue of national pride and prestige, and the Anglo-French agreement meant that once the ball had started rolling, the project was much harder to stop.34

It is tempting to think that money already spent on a project would be ‘wasted’ if you walk away from it. But the rational position on any investment would be to consider only the prospects of it turning a profit against future costs. It should be the same decision regardless of whether you are embarking on a fresh venture or have already invested in one. If a stock in your portfolio is dropping in value, you should sell it, regardless of how much you originally bought it for or how long you’ve had it. Sure, it may rally and bounce back. But there are also costs to having your capital invested there rather than in some other stock that is likely to continue rising in the near-term future. If humans acted rationally, past investment would not influence future decisions. 35

If a project is hitting significant problems and the costs are spiralling, the rational response is to cut your losses and walk away. There’s no sense in throwing good money after bad. Even if your bloody-mindedness sees the project through to completion, you’ll still have made a loss on the venture. And this is exactly what happened with Concorde: the costly development was continued long after it became clear that the economic case had disintegrated and the project was unlikely ever to return a profit.

It’s a particularly telling example of a cognitive bias known as the ‘sunk cost fallacy’: the tendency to continue an endeavour once an investment has been made, even after it becomes apparent that the outcome is unsatisfactory. But it has also become known as the Concorde fallacy.36 The British and French teams behind the project would have done well to heed the words of comedian W.C. Fields: ‘If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. Then quit. No use being a damn fool about it.’

The sunk cost fallacy is also a powerful influence locking nations into ongoing war, long after the possibility of achieving the original objectives has receded and the costs continue to rise. The US involvement in the Vietnam War stretched to twenty years before the fall of Saigon in 1975, spanning the administrations of five presidents (both Republican and Democrat): Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. Repeated congressional debates approved the continuation of the war, in part so that the dead would not have died in vain. Yet the longer the war was perpetuated, the more difficult it became to accept the tremendous losses with nothing to show for them.37 Still, not wanting the sacrifices to have been in vain is particularly perverse reasoning for risking even more lives.

Forty years later, the US once again found itself drawn into a protracted war with no end in sight. Following the September 11th attacks in 2001, the US-led coalition launched its war on terror and invaded Afghanistan, principally to topple the fundamentalist Taliban government and target Osama bin Laden and his al-Qaeda organisation. After sixteen years of military intervention, and still no clear pathway to an ultimate victory, President Trump declared in August 2017 that he would expand the US military presence and keep US boots on the ground indefinitely.38 While there were good reasons for attempting to secure stability and security in the country, the rhetoric used to justify the continuation of a US presence ‘after the extraordinary sacrifice of blood and treasure’ very much reflected the sunk cost fallacy: ‘our nation must seek an honorable and enduring outcome worthy of the tremendous sacrifices that have been made, especially the sacrifices of lives’.39 When the United States withdrew its forces in August 2021, the war in Afghanistan had become the longest conflict in US history, surpassing even the Vietnam War. The result was that the Afghan security forces quickly collapsed, and the Taliban reclaimed the country.

LOSS AVERSION

Another deep-seated cognitive bias that influences many of our more complex interactions, and consequently has played a powerful role in international relations and conflicts, is that of loss aversion. There is a fundamental asymmetry in the values we ascribe to equivalent losses and gains. Noticing that you’ve misplaced (or had stolen) £100 creates a much greater displeasure than the pleasure you experience winning £100 in the lottery. Losses loom larger than gains.40

In fact, psychological experiments using economic games have been able to quantify this imbalance. They have found that losses typically weigh 2–2.5 times more heavily on people than gains. As a result, we re-adapt much more quickly to positive changes in our lives than we do to negative ones. For example, our overall happiness returns to a normal level much sooner after a pay rise than a pay cut.

Loss aversion underlies other cognitive biases, such as the ‘status quo bias’ and the ‘endowment effect’.41 The former manifests itself in our general preference to stick with the current state of affairs rather than pursuing an alternative, because we fear the potential losses of switching more than we anticipate the potential gains; this opposition to change forms the psychological basis of conservatism. The endowment effect describes how we feel more strongly about holding on to an item that we possess than about acquiring such a thing in the first place.

These biases also have a strong influence on the risks we’re willing to accept when we have to make a decision in uncertain circumstances. The human appetite for risk varies depending on whether we consider the chances of making a gain or suffering a loss. (There’s also variation between personalities, but that’s a different issue.) When considering a potential gain, we prefer the option that offers a greater chance of a small gain over the one that offers a less probable but larger reward. We’re therefore risk-averse when it comes to making gains. For example, we tend to opt for the chance to win £10 based on a 50/50 coin toss rather than £40 from a one-in-six dice roll. This goes against the strictly economic expectation that a perfectly rational person would pick the dice roll because it has the higher average payout (£6.66 vs. £5).

On the other hand, our preference reverses and we have a tendency to be risk-seeking when we face the prospect of suffering a loss. We pick the option that offers the chance of minimising our loss even if it is less likely to occur compared to the alternative. So if we’re already in the red, we’ll take bigger gambles in an attempt to recover our losses so far. This tendency towards risky behaviour when we feel like we’ve been losing compounds the sunk cost fallacy we looked at earlier.

This shift in risk appetite makes sense in an evolutionary context. In the natural environment of our ancestors, losing food or another resource could mean the difference between life and death. When our survival is at stake, it makes sense to take larger risks: desperate times call for desperate measures.42

Our understanding of these related cognitive biases – loss aversion, the status quo bias and the endowment effect – has been combined into something of a grand unified theory of how we make decisions in conditions of uncertainty. Prospect theory is founded on experiments of how people actually behave when making decisions and judgements, in contrast to previous models of decision-making based on traditional economic thinking that viewed humans as perfectly rational calculators. It was developed in 1979 out of the long-running research programme on the interface between psychology and economics conducted by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky.43 Kahneman went on to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002 (Tversky had died six years previously and the Nobel is never awarded posthumously) for his work on human judgement and decision-making under uncertainty that is largely responsible for the creation of the field of behavioural economics.44

At the very core of prospect theory lies the human tendency to be loss-averse, and it shows that such cognitive biases have important consequences, in particular for bargaining and negotiations. Take negotiations of international trade agreements, for example. These involve discussions between nations to reach an accord on details relating to the taxes and tariffs that will be applied on different commodities or manufactured products, as well as quotas or other restrictions and the penalties for infringements of the terms. Securing an agreement involves each side making concessions to the stipulations and demands of the other. For each nation, the concessions made to the other side represent losses, whereas the concessions granted by the other side are gains. But because of loss aversion and the asymmetry in how we evaluate our own losses and gains, both sides can feel that their own concessions are not adequately balanced by those from the other party. The result is that both sides expect the other to offer up more than they themselves are willing to concede, and the cognitive bias can often make it difficult for negotiations to reach a successful conclusion.45

The situation is even more acute when a nation’s security, or even survival, is at stake. From the early 1970s, for example, the superpowers of the US and the USSR (and later Russia) negotiated a series of bilateral agreements on strategic nuclear arms to reduce the number of warheads, as well as the ballistic missiles and long-range bombers required for delivering them to targets, that each had in their arsenal.46 The talks often hit a stalemate, and breakthroughs took years to negotiate. Part of the problem was that their respective weapons systems were not directly comparable – in terms of their yield, accuracy or range – and required complicated horse-trading over, for example, how many of a particular kind of US ballistic missile would fairly balance those possessed by the USSR. But the psychology of loss aversion also played a powerful role: each side perceived a greater loss from the dismantling of their own nuclear missiles than the gain in security from an equivalent reduction made by their rival, and so felt disadvantaged by each deal on the table.47

The same cognitive biases make it much harder in international relations to pressure another state into discontinuing a course of action than to enforce their inaction in the first place. The endowment effect means that a nation will resist giving up something it already possesses much more fervently than another nation will seek to acquire it.48 For example, since the Second World War, eight states have developed nuclear weapons: the US, Russia, the UK, France, China, India, Pakistan and North Korea. Israel is also widely believed to possess a nuclear capability but refuses to acknowledge it, instead pursuing a policy of deliberate ambiguity. So far, the Non-Proliferation Treaty has successfully prevented any of the other nearly 190 sovereign states developing a nuclear weapons programme. However, only one country has developed its own nuclear arsenal and voluntarily given it up – South Africa, which assembled six nuclear weapons under the Apartheid regime but dismantled them all before the election of the African National Congress into government in the early 1990s.49 (And after the dissolution of the USSR, the former Soviet states of Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan all transferred the nuclear arsenals located in their republics back to Russia.)

Prospect theory emphasises that people tend to evaluate their gains and losses not in absolute terms but relative to a particular reference point, and this is often the status quo – what they currently have. In the case of nuclear disarmament, the US and the USSR at least had a pretty good idea of the numbers of weapons each other possessed, but conflict resolution becomes much more difficult when the two sides have different ideas about the relevant status quo because of a long and convoluted history of possession. This is often the case in territorial disputes which become all the more entrenched and bloody when rivals lay claim to the same land that has changed hands back and forth in the past. In the Middle East, for example, both the Israelis and the Palestinians lay claim to the West Bank on the River Jordan and the Gaza Strip, and each perceives the other as the aggressive intruder on their historical lands. In any attempt at resolution, no matter how the territory is divided, both sides feel an acute loss from their perceived status quo that greatly outweighs gains received from the deal.50

A similar situation occurred in Northern Ireland, and here the negotiation of the Good Friday Agreement is a good example of how prospect theory shows such conflicts can be peacefully resolved.

Ireland was partitioned by the British in 1921 to create Northern Ireland with a majority of unionists and loyalists who wished to remain in the United Kingdom and, as descendants of seventeenth-century colonists from Britain, were mostly Protestant. The southern part of the island was designated the Irish Free State – and later became the Republic of Ireland – containing mostly Catholic Irish nationalists who wanted a united, independent Ireland. Tensions persisted, with the significant minority of Catholic nationalists in Northern Ireland feeling discriminated against by the unionist governments. Mounting unrest led to the outbreak of sectarian violence in the late 1960s known as the Troubles. After thirty years of conflict, lasting peace finally seemed possible in April 1998, with a deal between most of Northern Ireland’s political parties as well as an arrangement between the British and Irish governments known collectively as the Good Friday Agreement.

The agreement covered a complex set of issues, including those relating to sovereignty, governance, disarmament and the security arrangements in Northern Ireland. The formation of a new assembly provided devolved legislature for Northern Ireland and a devolved executive with ministers from across the political spectrum. Institutions were put into place to ensure greater coordination on policies between the northern and southern jurisdictions, as well as a council of British and Irish ministers to enhance cooperation. And in order to end sectarian violence, paramilitary groups were to commit to the decommissioning of weapons in return for the early release of paramilitary prisoners, reforms to policing practices and a reduction in the presence of the British armed forces to ‘levels compatible with a normal peaceful society’.

The Good Friday Agreement was hugely significant as it was mutually acceptable to the two political groups – unionist and nationalist – which had diametrically opposed goals for the end state of Northern Ireland, and it offered a solid chance at peace after one of the longest-running conflicts of modern history. But not only did the opposing political leaders need to reach an accord, they then also had to sell the deal they had brokered to the public for it to be ratified by referendum.51 So what can prospect theory tell us about why the Good Friday Agreement was a success – in terms of both political accord and popular support?

As we have seen, one major insight of prospect theory is that people tend to be much more strongly motivated by what they could lose in making a decision. So the most effective way to avoid loss aversion sinking an agreement, and indeed to exploit its effects, is to present an option as the best alternative to a probable loss.52

The key to the Good Friday Agreement was that both unionists and nationalists saw it as the best chance for avoiding the loss of the security gained since the paramilitary ceasefire and of significant potential economic improvement. And most importantly, both the unionist and nationalist leaders were able to frame the agreement in a way that would be supported by their followers. The unionists argued that it was the best solution to avoid yielding sovereignty to the Republic while also strengthening the union between Northern Ireland and Great Britain. The nationalists, on the other hand, stressed that the agreement delivered equality for all citizens of Northern Ireland, and while not representing the end of the struggle for a united Ireland, it offered better political means for achieving this republican goal. The Good Friday Agreement deliberately didn’t engage with the question of the future of Northern Ireland – whether it should remain in the Union or unify with the Republic – so that both sides were able to rally behind it and the discussion could focus on what they stood to lose if the agreement failed.53

A month after the agreement had been signed by most of Northern Ireland’s political parties, as well as the British and Irish governments, a referendum was held for it to be publicly ratified. The Yes campaign secured a large majority of the votes in both parts of Ireland, and while the complex implementation of the agreement was not without difficulties, peace has held for over twenty years.